Nubank

The largest neo-bank outside Asia, with 100m customers.

You can find this write-up in pdf here → bit.ly/RedBeryl_Nubank

Nu Holdings is the bank-holding company for Nubank, the largest neo-bank outside Asia with 100m customers. Nubank is based in Brazil, where it continues to grow at ~60% p.a., and has recently entered Mexico and Colombia, where it is accelerating from a low base.

27% of the adult population in Brazil currently use Nubank as their primary bank account. In 2023 it turned profitable, currently achieving 60% RoE in Brazil. With a $57Bn market cap, the company is trading at 24x Run Rate Earnings for Q4-2023 (after share-based comp and exceptionals).

We believe Nubank is no longer a Fintech, but has become a full-service digital bank. It has a strong moat in the form of low cost to serve and proficient credit underwriting, and, in our view, a long runway for growth. Also, we believe that risks are lower than the term “neo-bank in Brazil” evokes, and we therefore recommend the investment.

Contents

Nubank’s fit with Red Beryl’s Investment Strategy

Opportunity Overview

Banking Industry in Brazil

Nubank’s Runway for Growth

Deep-Dive into the Mexican Opporunity

RoE, Profitability, Valuation and Long-Term Potential

Compeitive Position and Moat

Risks

Conclusion

1. Nubank’s fit with Red Beryl’s Investment Strategy

Nubank is an important company for Red Beryl. It is one of the largest holdings in our portfolio and our first write-up ever. It configures, nonetheless, a severe deviation from our intended investment strategy.

Red Beryl is a small investment partnership and, as such, we have a key advantage over other money managers in that we can invest in illiquid stocks. We spend most of our energy evaluating companies with little float, slim trading volumes and market caps in the hundreds of millions.

Also, we have no particular interest in Emerging Markets. We understand that equities are often optically cheaper in these realms, but we feel incapable of adequately determining which is the appropriate discount we should require for this type of risk, and we often find that the discount offered by the market is not necessarily far from our initial intuition.

For all these reasons, Nubank is exactly the kind of company we would usually avoid spending time on. It has a market capitalization of $57Bn, an average daily trading volume of more than $100m, it is based in Brazil, it is by no means hidden (even Berkshire Hathaway invested in its IPO, with Bill Ackman later publicly quizzing Berkshire’s Todd Combs for his views on the stock), and trades at a hefty 24x Q4-2023 Run Rate Earnings.

However, we believe that it is a company operating within an incredibly unique set of circumstances that make it a true long-term compounder with fantastic moats and significantly less risk than the term “neo-bank in Brazil” evokes. We do not have a good answer as to why “alpha” might exist in such a well-researched opportunity, and we recognize that in a negative macro environment the stock is likely to re-rate significantly more than others. However, we hold a strong belief that in 10 years Nubank will be worth a lot more than it is now and, as such, we have gladly made an investment, even if it fits none of the traditional attributes we are looking for.

2. Opportunity Overview

Having recently crossed the mark of 100 million customers, Nubank is the largest neo-bank outside Asia. It operates primarily in Brazil but has recently expanded into Mexico and Colombia. It was founded in 2013 by David Velez, a Colombian entrepreneur who, after receiving an MBA from Stanford, joined the Venture Capital firm Sequoia to cover Latin America. Two years later, he recognized the opportunity to establish a digital bank in Brazil, received seed funding from Sequoia and set up Nubank. The performance of the company has been exceptional since inception, and the company turned sharply profitable in 2023.

Nubank started by offering a fee-free credit card. In 2017, it obtained a banking license, and soon after launched a checking account. Together with personal loans, these 3 products are the source of more than 90% of the Revenues today. Nubank does not aim to be a point-solution like most Fintechs in the US and Europe, but instead is on a journey to build a full-service bank offering able to compete head on with incumbent banks.

To this date, Nubank has achieved widespread adoption in Brazil, with 53% of the adult population currently signed up as a customer, 44% an Active customer and 27% using Nubank as their primary bank account.

In our view, there are 4 key elements that have driven Nubank’s success:

I. Structure of the Banking industry in Brazil: with the top 5 banks holding over 80% market share, consumers in Brazil used to be poorly served. Abusive fees were highly prevalent and interest rates on debt were sky high (400%+ p.a. on revolving credit card and 150%+ p.a. on personal loans). As a result, Brazilian banks achieved very high RoEs (over 20%), even if doing little to increase operational efficiency.

Nubank’s initial product was simply a fee-free credit card with an easy-to-use app and great customer support. It was met with exceptional enthusiasm by customers, who were used to queuing for hours in heavily armoured bank branches to obtain a credit card, which would have at least ~$50-100 in annual fees.

II. Lower Cost to Serve: traditional banks in Brazil operate with large amounts of overhead, managing thousands of branches and workforces in the region of 80-100k employees each. Nubank, with roughly the same number of customers today as the largest traditional banks, operates with only 8k employees. Nubank passes those lower costs to its customers, resulting in lower fees and interest rates, and hence attracting more customers and higher usage.

III. Ability to Underwrite Credit: Nubank is a fully licensed bank, with the ability to accept deposits and use them to extend loans. Originally, the main source of Revenue was interchange fees (~1.2% of the Purchase Volume) but since inception Nubank has understood that banking in Latin America revolves around extending credit. Interest on Loans represents a much larger profit pool than fees (see Figure 2), and offering credit products is the only way to become the primary bank account for a majority of the population.

Underwriting credit is, however, notoriously difficult, with several start-ups having recently tried and failed (a recent example in Brazil is Stone Co). Over the last 10 years, Nubank has built a highly sophisticated credit operation inspired by Capital One, which in the 1990s developed a new way of underwriting consumer credit in the US that consisted in performing complex data analyses to determine the repayment likelihood for each customer. Interestingly, Nubank’s current COO is the former Head of Card Analytics and Infrastructure at Capital One.

As a result, in the last decade Nubank has amassed a ~$18Bn Consumer Credit Portfolio spread across ~40m customers, providing an invaluable amount of proprietary data on the performance of different credit cohorts across the cycle. That serves as a significant moat against new start-ups, and reduces the once meaningful gap vs traditional banks.

IV. Overall great execution: across this report we will present several examples of Nubank’s ability to ramp-up new products and geographies, recruit a top tier US-centric management team and achieve high NPS across its products. Overall, Nubank’s execution to date is impeccable, with no major missteps, and far outcompeting similar start-ups.

The reader might be surprised that “great Customer Experience” does not feature more prominently as one of our key reasons for explaining Nubank’s success. When looking at neo-banks in the US and Europe, an intuitive and easy to use app is often one of the main selling points. In our view, that explains the lack of traction of neo-banks in these geographies (we urge the reader to try to find a digital bank in the US or Europe meaningfully taking share in core banking products, such as deposits, loans or credit cards). Start-ups like Chime or Revolut have great mobile apps, but they are not comparable to Nubank, given their very shallow offerings and inability to displace traditional banks as primary banking providers.

In contrast, in Brazil 27% of the adult population uses Nubank as their primary bank. We believe that this success is not primarily driven by having a great mobile app, which they have. Instead, what Nubank has achieved in Brazil is driven by charging lower fees, lower interest rates and sustainably providing credit to customers that other banks would not underwrite.

“In Brazil, when you need a credit card, you just go to all the main banks and ask for one. Usually only one or two approve you, so those are the ones that you use, ideally the one with the lower fees. It has little to do with anything else” – Former Nubank Director of Corp. Dev.

To this end, Nubank has mastered the low-and-grow approach to credit limits pioneered by Capital One, which revolves around on-boarding unknown customers by offering a very low credit limit to start with (often as low as $10). Progressively over time, as customers show their willingness and ability to repay debt, credit limits are expanded. The result is the cohort behaviour shown on RHS of Figure 3, where customers’ usage, and thus ARPAC, increases systematically over time.

Among the big banks in Brazil, Nubank is the best positioned to implement a Low-and-Grow approach, given the lower cost to serve. As the reader can imagine, serving a customer with a $10 credit limit is hard to do profitably from a branch. This has historically resulted with a moderate skew for Nubank towards lower income customers than traditional banks. However, with 53% of the current adult population being a customer of Nubank, its customer distribution is slowly converging to other banks’, even if Nubank’s Share of Wallet is still lower for high-income individuals (more on this later).

Nubank’s success has left its founder, David Velez, with a fortune worth more than $12Bn. Alignment of interests is strong, with the majority of his wealth fully invested in Nubank (he owns ~20% of the company). Share Based Compensation is minor and fully expensed into the presented Net Income figures and, as a further proof of good corporate behaviour, in Q4-2022 David Velez voluntarily surrendered (with nothing in exchange) a Long-Term Incentive Package that was awarded to him at IPO.

Throughout this write-up, we will expand on each of the five pillars of our investment thesis:

I. Nubank has a very strong moat and competitive positioning.

II. The runway for growth is long, with end-state potential earnings of $4/share (vs spot price at $11.76/share).

III. RoE is already as high as 60% in the Brazilian subsidiary (other Geos still loss making).

IV. Valuation is more attractive than headline figure suggests, trading at 24x Q4 2023 Run Rate Earnings, when adjusting for the accounting impact of IFRS 9.

V. Risks are much lower than initially apparent, particularly macroeconomic and credit risk.

Note that we have chosen to present valuation on an Earnings Multiple, not on a Book Value Multiple. At $11.76/share Nubank trades at a very high BV multiple of ~9x. However, with a RoE of 60% in Brazil, we believe that Book Value becomes meaningless. For context, below we compare the RoE of Nubank vs that of well-known US tech companies. We believe the reader is likely to agree that valuing Amazon on a Book Value basis is inadequate, and we argue that the same is true also for Nubank.

3. Banking Industry in Brazil

Brazil has well-developed financial markets, with a functioning regulatory framework and an increasing adoption of credit. Over the last 15 years, household debt to GDP has more than doubled, leading to significant market growth, with a long runway ahead if the gap vs developed markets is to be progressively reduced.

The market has historically been very concentrated on the Top 5 banks (Itau, Banco Bradesco, Banco do Brasil, Banco Santander and Caixa Federal). They used to hold 80%+ of the total market, both in Consumer and Commercial. As a result of the lack of competition and limited capital availability, the Brazilian banking industry is among the most profitable ones in the world.

However, powered by the advance of smartphones, a number of digital disruptors led by Nubank have emerged and started to capture market share on the consumer side. The commercial side remains undisrupted.

As seen on Figure 8, on the consumer side, the main types of loans are credit card, personal loans and payroll loans. The reader is likely to be surprised by two factors. First, that interest rates are obnoxious by US or European standards, which is the result of a stark lack of competition combined with a high level of delinquencies (more on this later). Second, that Mortgage is a much smaller asset class, which is due to the fact that banks have historically struggled in court to enforce foreclosures. Also, given the very high interest rates on other loans, Mortgage holds an even smaller weight in the total revenue pools.

To set the scene, and given significant differences vs the US and Europe, a detailed description of the structure of the three main types of consumer loans feels appropriate.

Credit card is the main form of financing for the average Brazilian consumer. When a consumer purchases an item, it has three ways of paying with the credit card:

I. Without instalments: if the consumer selects this option, the purchase will be completed instantly and debited from the consumer’s account (on average) 28 days later without any cost to the consumer. The bank receives an average interchange fee accounting for ~1.2% of the purchase value, which is discounted from the amount paid to the retailer (same as in the US and Europe).

Unlike in the US and Europe, however, the retailer does not get paid instantly for the transaction. Instead, the funds are transferred by the bank to the retailer 30 days later. Therefore, given the bank is paid 28 days after the transaction but only pays the retailer after 30 days, a basic credit card transaction in Brazil generates 2 days’ worth of funds for the bank, as opposed to consuming funds like it does in the US and Europe (and in Mexico, more on that later).

If when the bill is due after 28 days the consumer does not satisfy it, the balance becomes “revolving”. Revolving balances can last, by law, only for 1 month, after which they need to be automatically converted into instalments. The revolving balance is notorious for having high NPLs and a very high average interest rate of 476%, as per Dec-23 Brazilian Central Bank data. The interest rate after the revolving balance is converted to instalments is lower, with an average of 192% p.a.

II. With interest-free instalments: in Brazil it is very common that retailers offer interest-free instalments. In this case, at check-out, the customer is presented with the option and, if selected, the purchase value is spread across 2 to 12 payments and debited periodically from the customer account over the following months.

In this case, the bank is remunerated with the same ~1.2% interchange fee as in the no-instalments option, and receives no interest, given the retailer is paid in instalments following the same pattern that the funds are debited from the consumer’s account (e.g. if the consumer pays 1/12th of the purchase value each month over 12 months, the retailer receives the funds following the same timeline).

However, the risk of default stays with the bank. Following the example above, if the customer defaults after 6 months, the bank is still liable for paying the retailer on time for the remaining instalments. This is a negative dynamic for banks, given they take higher credit risk than in the no-instalments option (the customer needs to stay current for longer) without being appropriately compensated for it (the interchange fee is the same and there is no interest). The high prevalence of the interest-free instalments option in the Brazilian credit card industry is often used as an argument by banks for the relatively higher interest rates in the interest-paying portion of the credit card portfolios.

III. With interest-paying instalments: if the retailer does not provide an interest-free instalment option, the consumer can choose to divide the purchase across several instalments with their bank. In that case, the bank pays the retailer 30 days after the purchase and debits the customer accounts over the coming months, receiving the interchange fee and interest for financing the purchase.

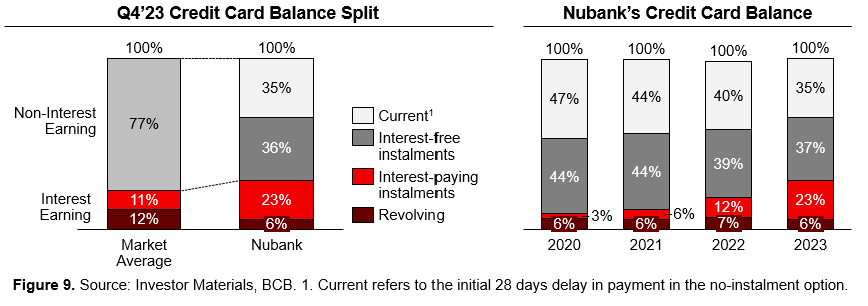

The chart above deserves three main comments. First, note that the credit card in Brazil is primarily a tool for financing as opposed to transacting, unlike in the US and Europe, where the majority of the balance is current (vs just 35% for Nubank). Second, note that Nubank presents a much lower share of revolving balance than the market (6% vs 12%). This is by design, since revolving introduces very high interest rates, low NPS and high NPLs. As such, Nubank actively tries to quickly structure its customers’ revolving balances into instalment products. Finally, note that as the credit cohorts mature, Nubank is expanding the interest-earning portion of their balance (29% in 2023 vs 9% in 2020).

Switching to the second asset class, personal loans have the same structure as in the US or Europe, where cash is advanced in exchange for interest payments. Interest rates are substantially higher though, with the market averaging 155% p.a. and Nubank averaging 114% p.a, as of Dec-23 Central Bank data. As an anecdote, figures are stated to the Brazilian consumer as interest per month (e.g. 6.5% p.m.), rendering the figure apparently more palatable.

Payroll loans, on the other hand, are a unique feature of certain Latin American markets, such as Brazil. In this case, banks extend credit to individuals and, through IT integration with government systems, the principal and interest payments are diverted automatically from the borrower’s government-sponsored monthly income. Naturally, this form of financing is available only to those perceiving recurring payments form social security (retirees and disabled individuals) or employed at a public entity (federal or state governments, municipalities, etc.).

These loans have a much lower interest rate (capped at 1.7-2% p.m. by law). Default rates are much lower and, importantly, stable and uncorrelated from the broader macroeconomic environment. Default on payroll loans occurs mostly under three scenarios:

I. A public sector entity (e.g. a small municipality) is no longer able to pay salaries. Note that banks usually limit lending to employees of public entities with doubtful creditworthiness.

II. Another financial obligation (e.g. taxes, child support or a lawsuit) gains seniority over the credit payment.

III. The borrower deceases and there are not enough assets left to settle the loan.

Given the lower interest rates and longer maturity of these loans (2-3 years vs ~6 months for personal loans), the only way to fund them profitably is by having access to a strong deposit franchise that is both low-cost and sticky. Since building a deposit franchise is difficult and time-consuming, traditional banks have seen little disruption in this market and retain a very high market share. Note that Nubank has, over the last decade, built a meaningful deposit franchise, having recently changed its remuneration policy to narrow the gap vs incumbents (with no impact to churn metrics). As such, Nubank recently launched a payroll lending product that is rapidly accelerating (more on this later).

A Banking overview would not be complete without a brief description of the dynamics around Deposits. Deposits in Brazil are similar to the US or Europe, with checking accounts that are (often) unremunerated, complemented with remunerated savings accounts and term deposits. The main singularity for Brazil is the fact that the Central Bank interest rate is much more volatile than in the US or Europe and often much higher. In result, the industry has evolved to pricing deposits not at a fixed rate but as a stated percentage of CDI (the Brazilian equivalent to SOFR). A typical deposit in Brazil will not pay “11% p.a.” but instead “100% of CDI”. This results in Deposits repricing instantly with changes in the interest rate environment, as opposed to the lag experienced in other markets. However, unlike the US, the very high Net Interest margins in Brazil and the relatively short asset duration have historically prevented major funding crises.

Finally, to conclude this section, we would like to include a few remarks on the Brazilian Banking Regulator, the BCB. Conscious of the need to reform the banking sector, given abusive fees and very high interest rates, the Brazilian Central Bank has been very open to fintech as a way to promote competition. From a regulatory perspective, though receiving no direct support, Nubank has found it easier to obtain the necessary licenses and permits in Brazil than other startups in similar countries, such as Mexico (more on that later).

An example of this benign regulatory environment occurred in 2017, when the Brazilian Central Bank blocked a proposal from the Federal Government to change the deadline for credit card issuers to settle transactions with retailers from 28 days to 2 days (see discussion on credit card above). That proposal would have aligned Brazil with international standards and protected retailers. However, the existing lag allowed Nubank and other start-ups, which started as credit card issuers without a banking license (and hence without the ability to accept deposits), to scale without a massive need for equity funding. Changing the settlement time would have benefited incumbent banks, who had access to strong deposit franchises, and hindered competition, which was clearly against the BCB’s stated goals.

More recently, the BCB has launched two highly innovative and disruptive frameworks focused on increasing competition, both of which Nubank is navigating effectively: Pix and Open Finance.

Pix is an instant payment system that launched in 2020, is centrally managed by the BCB, and allows businesses and individuals to execute account-to-account payments in a free, fast, and easy manner. It has experienced explosive growth, cannibalizing primarily cash payments (52% of POS Payments in 2017 vs 22% in 2023, as per The Global Payments Report from Worldpay/FIS).

Initially Pix was mostly used for peer-to-peer transfers, but over time, businesses are allowing payment using Pix (payment can easily be executed by scanning a QR code). That bears the natural question on whether Pix will eventually disrupt debit and credit card payments. We admit that this is tough question to answer, but we offer a few thoughts:

I. Businesses prefer to be paid using Pix, given no interchange fee is involved.

II. However, we have argued before that credit cards in Brazil are a financing tool, not a transacting one, so Pix itself should not be able to disrupt credit cards, but…

III. ...financing for Pix is a reality and Nubank currently allows customers to use their credit card limit to finance their Pix transactions in exchange for interest payments. Nubank has been the first major bank to launch this product, allowing it to increase the interest-earning instalments portion of their credit card receivables (23% for Nubank vs 11% for the Market, as shown in Figure 9).

IV. The above argument does not apply to debit cards, which are clearly at risk of disruption by Pix.

We do not know if Pix adoption will reduce debit and credit card adoption. If it reduces debit card adoption it will impact Nubank’s debit-card-related interchange fees, which account for ~3.5% of their total Revenues. If it reduces credit card adoption, we believe there should be no impact on Nubank’s profitability, given (i) much clearer leadership on Pix financing than generally on credit card and (ii) there is no reason why Pix financing should overall be a less profitable product than credit card. Sure, it does not include interchange fees, but we remind the reader that 71% of Nubank’s credit card balance is interest-free (Figure 9), vs none for Pix financing.

Overall we believe Pix is a great case study of the financial innovation happening in Brazil and how Nubank is navigating it. First, it reduced cash usage, which is positive for a player with no branches or native ATMs like Nubank. Second, it allowed Nubank to differentiate by launching Pix financing faster than incumbents. And finally, it showcases Nubank’s great execution by observing Nubank’s market share of Pix keys, which is significantly ahead that of all other incumbent banks.

In order to execute a Pix transaction, an identifier of the destination account is needed. That identifier is called a Pix key. The user can choose what that key looks like. It can be an email address, a phone number or an alias.

When Pix was released in 2020, there was a fierce competition among banks to capture Pix keys. Banks correctly anticipated that if customers associated their preferred Pix key (e.g. their phone number) with their bank account, that would drive increased usage of that bank account.

In 2020 Nubank counted only ~15% of the adult population in Brazil among their customers vs ~40-60% for each of the large banks (individuals in Brazil often have multiple bank accounts). Hence, gaining market share of Pix keys was, in principle, much harder for Nubank. However, after designing the best sign-up experience in the industry, Nubank managed to capture more keys than any of the incumbents, using the Pix opportunity to accelerate growth.

“We bet big on Pix, and we sweat every pixel of the sign-up flow, because customers were going to decide who would get their Pix keys. We drove our team crazy to make it as simple as we possibly could. That has been a key driver of our recent growth.” - Jag Duggal, Current CPO at Nubank.

Finally, the dynamics with Open Finance are similar to those around Pix. The Brazilian Central Bank launched in 2021 a regulatory framework by which customers could transfer their data from one financial institution to another. The goal was to increase competition for the incumbent banks, who held the very valuable historical transaction data that is used for underwriting credit. Having access to that data allows newcomers, like Nubank, to offer credit with better terms to those customers.

Getting customers to approve the transfer of data and incorporate it into the underwriting flow is, however, not easy. As with Pix, Nubank has executed better than the incumbent banks and, as can be seen below, leads by a wide margin the number of successful incoming data transfers.

Note, however, that the set of data available through Open Finance is limited and that we believe that underwriting credit is an incredibly complex endeavour. As such, based on conversations with industry participants, we believe Open Finance will not meaningfully erode Nubank’s moat around Credit underwriting vs newer Fintechs (e.g. Mercado Pago), even if it is definitely a negative element on that respect. More on that later.

4. Nubank’s Runway for Growth

A key element of our investment thesis is that Nubank has a very long runway for growth, very high visibility on that growth, and that little capital will be consumed due to high RoEs. In this section, we address the 7 growth drivers that we believe will drive Nubank’s top line over the next decade:

I. Increase in number of customers.

II. Increase in per-customer usage of credit card and personal loans.

III. Rollout of payroll loans.

IV. General market growth.

V. Increase in penetration within the high-income segment.

VI. Rollout of adjacent products.

VII. Geographical expansion.

Starting with the increase in the number of customers, Nubank has consistently been adding 4-5 million new customers in Brazil every quarter for the last 3 years. This growth avenue will eventually tap out, but we believe it is likely that some more quarters of customer growth in Brazil remain ahead. For reference, management has guided to 100 million active customers in Brazil alone (vs 73m active customers in Q4-23).

Given the low-and-grow approach we discussed above (see Figure 3), existing customers unlock higher credit limits over time, which results in the increase in usage for credit card and personal loans seen below. Together with net customer growth, this has been, and is expected to continue be, the main driver of Nubank’s growth in Brazil.

To calibrate the runway for increased usage, note that currently Nubank is the primary bank account for 27% of the Brazilian Population, but only captures 7-13% Market share for credit cards and personal loans. Management has stated that there is no reason why, in the long term, that market share should not converge towards principality, and intuitively we agree. If that happens, credit card revenues could ~2x and personal loans could ~4x.

As a second triangulation, see below a comparison for Monthly Average Revenue Per Active Customer (ARPAC) between Nubank and incumbents. As discussed in Figure 8, credit card and personal loans (together with payroll loans) are the main contributors to revenues. Nubank is currently at a fraction of incumbents’ ARPAC, therefore suggesting opportunity for growth. Management has indicated that they do not expect to achieve the same ARPAC as incumbents, given lower fees and lower share of wallet with high-income customers, but feel that $25-30/month should be achievable in the medium term. If true, that would support significant expansion in credit card and personal loans.

This leads to the third pillar of growth: rolling out payroll loans. Nubank has recently launched a payroll loan offering that, according to management “has been met with absolute enthusiasm”. Like all Nubank products, the distribution is entirely digital, which in the case of payroll loans is particularly relevant given the Brazilian market is still heavily reliant on brick-and-mortar brokers (locally called “Pastinhas”), which account for ~40% of the payroll loans originations.

We believe Nubank’s Payroll offering is likely to succeed because of the following reasons:

I. Nubank D2C distribution eliminates origination fees and, together with offering a lower interest rate than incumbents, results in an overall better proposition for customers.

II. In April 2024 Nubank started accepting portability of payroll loans and, leveraging Open Finance (see Figure 13), is targeting customers with high-interest balances at other financial institutions, proactively offering the opportunity to easily port the loan to Nubank and obtain a lower interest rate.

III. In an environment of declining interest rates (see RHS of Figure 11) the dynamic described above is particularly powerful, given payroll loans are fixed rate.

IV. ~40% of all payroll loans in Brazil are currently drawn by individuals that already have a Nubank bank account, as per management commentary. Therefore, this is primarily a cross-selling exercise to the existing customer base.

Payroll loans is a large, but less profitable asset class than credit card and personal loans. Doing a quick back of the envelope math, if Nubank achieves 10% market share, that would translate to a ~$13Bn portfolio, which at a ~18% annual interest rate, ~8% cost of deposits and ~2% Charge-off rate, yields ~$1Bn of pre-tax income, which is small when compared to Nubank’s $57Bn current market cap. However, payroll loans are a key product that Nubank was missing until recently, and we believe that offering it is likely to increase principality and add to the competitive moat vs other digital players.

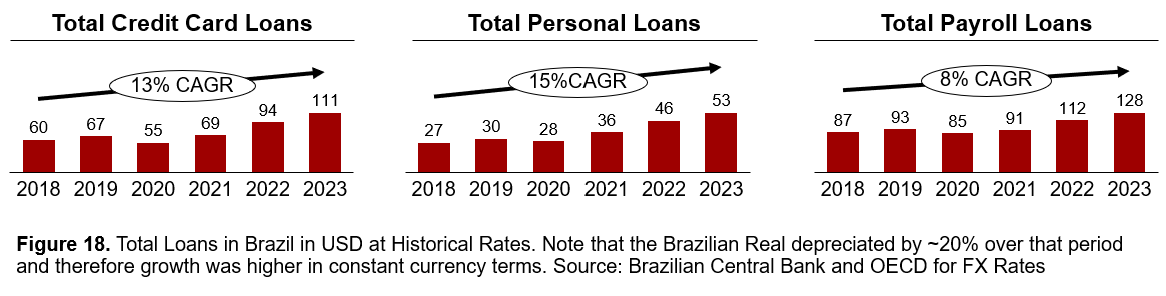

Across credit cards, personal loans, and payroll loans, Nubank has a clear opportunity, in our view, to gain market share. However, it is important to note that all these products present a fundamental tailwind in the form of general market growth, the fourth pillar of growth. Total outstanding balances in Brazil have grown, in USD, at 8-15% p.a. over the L5Y. This reconciles with Figure 6, which shows the increasing household debt as a percentage of GDP and the still significant gap vs developed economies. Based on our conversations with industry participants, this growth is generally expected to continue over the next few years.

The fifth pillar of growth revolves around the opportunity to increase penetration within the high-income segment. According to management, Nubank already counts among its customers ~60% of the high-income population in Brazil. The figure reconciles with the LHS of Figure 4. However, to this date, Nubank has struggled to drive usage from this customer group, lagging incumbent banks in Share of Wallet.

I always use my credit card from Itau, as opposed to the one from Nubank. They give me a much higher credit limit and there are a lot more ways of using my cash-back points. On high-income, Nubank is clearly behind, even when comparing to much smaller start-ups like C6. –Cofounder of Drip, a fintech startup in Brazil.

Over the last few quarters, Nubank has been developing their high-income offering, called Ultraviolet, which is free for customers that spend more than $1k per month on their credit card. They have finetuned their credit models to increase limits for this segment, implemented a cash-back offer, signed partnerships with companies like Rappi and HBO, and started adding functionalities like a low-cost multi-currency bank account designed for foreign travel. As a result, the purchase value on their Ultraviolet credit card has increased 2x over the last year to $1.1Bn in Q4-2023, but still constitutes only ~3.5% of Nubank’s total purchase volume.

We intuitively believe that Nubank will likely be able to develop, over time, a high-income offering comparable to that of incumbent banks. They could also choose to share part of the cost to serve differential vs incumbents in the form of better cash back or incentives. However, we admit that we are unsure about the role of Brand in this segment. Nubank is perceived in Brazil as a mass market brand, and we could see a world where high-income customers refuse to use Nubank for what the brand evokes, in a similar way that we would put only so much credibility on a theoretical Capital One’s bid to compete with American Express in the US. Our conversations with industry participants in Brazil have yielded different answers to this question, and our understanding of the behaviour of the Brazilian consumer is not deep enough so that we can fully underwrite Nubank’s ability to win in this sector. Therefore, we treat this growth opportunity as an upside.

The sixth pillar of growth revolves around Nubank rolling out adjacent products. In management’s view, consumers in Latin America tend to concentrate the purchase of all financial services in one provider, and Nubank is therefore striving to become a full-service platform. The main products they are currently rolling out are:

I. Insurance: their core offering to date is life insurance, which they offer through a partnership with Chubb. They are currently developing car insurance and home insurance products, which are in testing phase.

II. Investments: In 2020 Nubank acquired Easyinvest, a digital broker in Brazil. After struggling more than expected with the integration, Nubank currently offers a full-service investment platform that includes stocks, bonds, ETFs, mutual funds, etc.

III. Cryptocurrencies: In 2022 Nubank started offering the possibility to buy cryptocurrencies through their app. For now, they offer 15 cryptocurrencies, including USDC, a stablecoin pegged to the Dollar that has received significant interest in Latin America.

IV. Shopping: Nubank’s mobile app includes a tab where customers can purchase e-commerce products from more than 200 retailers. Nubank captures a price per lead and leverages its 90m customers in Brazil to obtain better offers for their customers. In 2023, Nu Shopping received 255m total visits.

V. BNPL: Nubank offers a BNPL product called NuPay, through which customers can easily check-out online and obtain additional financing options. Currently the product has 3.5m users and is accepted by 9% of the Top 150 retailers in Brazil, as well as apps like Uber or iFood.

VI. SME Accounts: Nubank counts among its customers millions of self-employed individuals and microentrepreneurs. To address their needs, Nubank has developed a “pessoa jurídica” offering that allows these individuals to set up a commercial bank account, receive a credit card, accept payments through the NFC reader of modern Smartphones, and manage their invoicing and tax workflows. To date, Nubank has 2.2m commercial users, and in March 2024 they announced an expansion into lending for this segment, by launching a Working Capital financing solution.

In general, the overall size-of-the-prize for these products is small. As of today, the fees associated with all the products above contribute about ~2% of total revenues (excl. SME credit card, which is not disclosed separately from consumer credit card). However, we believe that they are a useful tool to increase principality and, thus, the value will arise from a higher usage of Nubank’s main revenue engines, namely credit card and personal loans.

To this point, all the drivers presented revolve around Brazil. This brings us to the last pillar of growth: geographical expansion. In 2019 Nubank expanded into Mexico, and in 2020 into Colombia. In 2023, Nubank obtained banking licenses to be able to accept deposits in both markets. We believe that the market dynamics is both cases are such that Nubank could replicate the same strategy as in Brazil and achieve similar levels of success. Combined, Mexico and Colombia have the same GDP as Brazil, so over time they can become meaningful contributors to the P&L.

On several interviews, Nubank’s founder has repeated that more countries will come in the next 2-5 years. Interestingly, he has stated that in a 5-year horizon, he envisions Nubank expanding outside LatAm. We admit we are somewhat puzzled by this assertion.

When looking at the remaining countries in LatAm, we intuitively believe they are all too small to warrant management losing focus on the very large runway remaining in the 3 countries where Nubank already operates. Banking is an extremely local endeavour, with varying legislations, types of products and needs for licenses. Therefore, we like Nubank’s current strategy of going narrow but deep (as opposed to other players, like Revolut, who chose a global but point-solution approach).

When looking outside LatAm, the obvious candidate for expansion would be the US, potentially seeking to target its Hispanic population (65 million individual). However, the US is a very different market, with highly sophisticated competition and comparatively very low interest rates on personal credit. We are unsure how could Nubank build a successful operation in the US without significant RoE dilution. If not the US, we admit we cannot imagine Nubank travelling to India or other developing markets where, on another hand, their product would likely have a better fit.

With any other management team we would likely be concerned with these remarks. But given Nubank’s exceptional execution track record to date and the full alignment of interests between Shareholders and the Founder, we feel inclined to give David Velez the benefit of the doubt also on this point.

5. Deep-Dive into the Mexican Opportunity

Nubank entered Mexico in 2019 and followed the same roadmap it did in Brazil 5 years earlier. Given accepting deposits requires a banking license, and this is a time-consuming endeavour, they started with a credit card offering. That had the benefit of being able to start acquiring customers while the regulatory dialogue progressed and, more importantly, to start adapting the credit underwriting models to a new geography.

The process to train these models starts by giving credit to a large number of customers with different backgrounds, observing how the repayment rate unfolds over the next couple of years and, eventually, looking for correlations between repayment rates and customer characteristics. This initial survey results in a heavily loss-making cohort, where the priority is not to maximize risk-adjusted returns, but to extract as much data as possible to train the credit models.

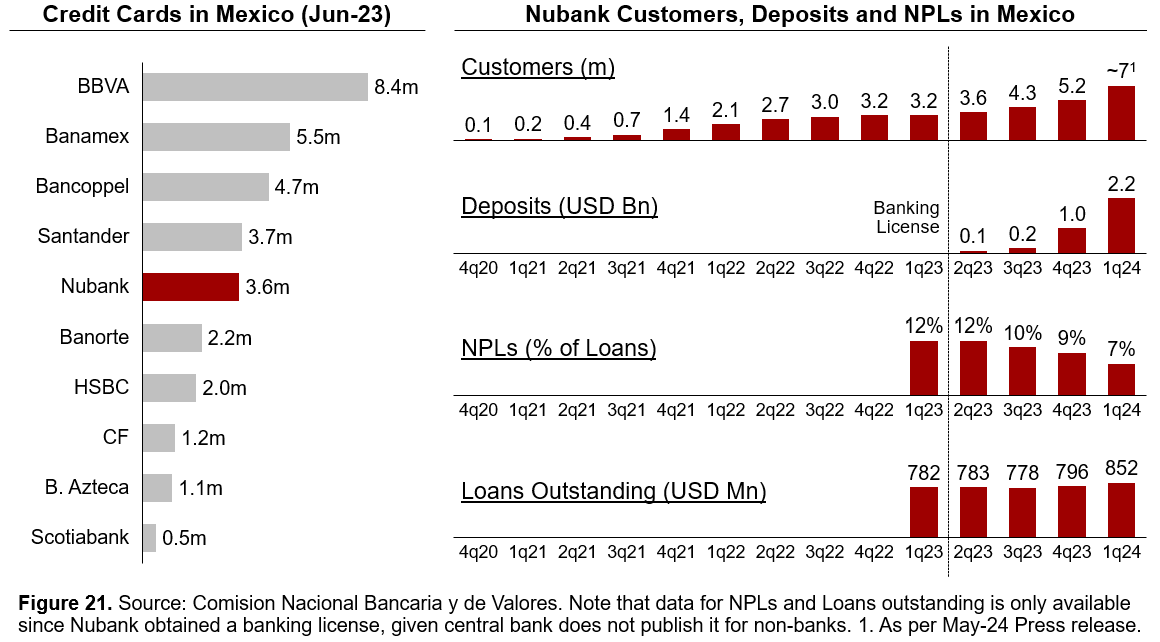

Hence, until Q2 2022, Nubank focused on acquiring as many customers as possible. Given incumbent banks charge significant annual fees for a credit card (e.g. BBVA currently charges USD50/year for the entry-level card), by simply offering a free credit card Nubank was able to generate significant demand.

In that period, Nubank climbed to position #5 in Mexico by total number of cards issued. Given that this initial cohort was not intended to obtain risk-adjusted returns but to gather data, and in order to cap the initial investment, Nubank reduced the approval rate for new customers, while waiting for the original cohorts to age and the credit models to improve. That created the slowdown between Q2 2022 until Q2 2023 seen in Figure 21.

In Q2 2023 Nubank was finally granted a Mexican banking license. That allowed to onboard customers even if not approving them for a credit card, given Nubank could offer instead a bank account with an associated debit card. Nubank therefore resumed customer growth, even if not yet expanding the loan balance (see below).

Overtime, the NPLs of the original credit cohort started to decline, as aging non-performing loans where progressively charged-off, the models improved, and the performing customers were retained. As such, Management has indicated its willingness to reaccelerate loan growth, which can already be seen in the recently published Q1 2024 Mexican regulatory filing.

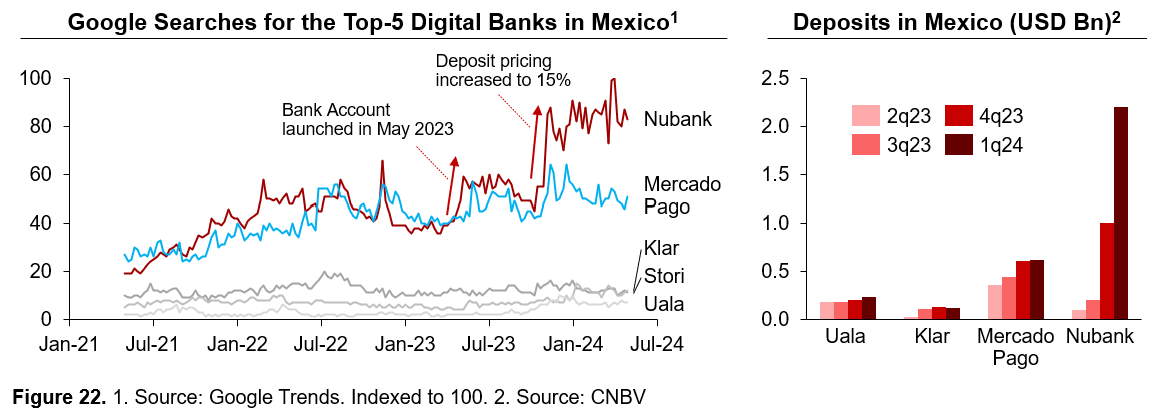

On the Deposit side, Nubank is pursuing a rather aggressive strategy. In November 2023, they announced they would remunerate deposits at 15% p.a. This compares with BBVA, Mexico’s largest bank, having an average cost of deposits of 3.7% p.a., as per Central Bank filings. This is a totally off-market rate, and the result can be seen in the explosive growth in deposits observed above, with deposits increasing 5-fold in Q4 2023 and 2-fold again in Q1 2024.

Nubank currently has $2.2Bn in Deposits and only $0.9Bn in Loans. Most of these loans respond to the current revolving balance of credit cards (and hence do not pay interest). However, the interest rate is high enough on the interest-paying portion of the credit card that the Net Interest Margin is still positive at 2%. The Mexican subsidiary, however, was overall loss making in Q1 2024, printing a $45m pre-tax loss (as per CNBV data) vs ~$400m positive net income from the Brazilian subsidiary (as per Jan-Feb BCB data).

Management has acknowledged that this is a large investment for Nubank. The path forward revolves around (i) expanding the loan book in Mexico to utilize those highly remunerated deposits and (ii) eventually decreasing the interest rate paid on deposits. Management believes that their offering is not yet mature enough in Mexico to be able to fulfil the entire needs of their customers, and hence they need to provide an alternative incentive. Once the offering is more mature, they intend to reduce the deposit remuneration, in line with what they did in Brazil in Q3 2022 (and which led to virtually no churn).

It is important to note that other digital banks are currently operating in Mexico. Klar, Stori and Uala are the 3 most prominent independent start-ups offering a credit card and a bank account. All of them have followed Nubank in offering remuneration rates around 15%. However, their offerings are gathering limited traction, as seen below. We believe it will be hard for independent start-ups to compete with Nubank because:

I. They lack Nubank’s financial muscle. Nubank has invested $1.4Bn to date in Mexico, and it is recycling a high proportion of the infrastructure and products developed for Brazil. In contrast, Klar and Stori have each raised less than $400m and need to build a new bank entirely from scratch.

II. Nubank has a decade of experience underwriting credit and has built one of the most sophisticated credit operations in the world. Being able to extend more credit to their customers is a key differentiation in Mexico, and based on our conversations with industry participants, Klar, Stori and Uala are at a much earlier point in their credit journey.

On the other hand, Mercado Libre, through their fintech arm Mercado Pago, is a formidable competitor. We will spend a lot of energy in Section 7 discussing about them, but for now it suffices to say that:

I. Mercado Pago launched in Mexico 3 years earlier than Nubank, and still has more active bank account customers than Nubank (~14m vs ~7m), even if the latter is closing in.

II. However, Mercado Pago does not have a banking license, and therefore cannot use deposits to fund loans. Hence, it can only offer a lower remuneration for Deposits (10% vs 15% for Nubank).

III. Mercado Pago historically struggled with credit underwriting across both Brazil and Mexico, and for now they act more as an electronic wallet than a full-service bank.

IV. However, Mercado Pago launched a credit card offering in February 2023, and they currently have 1m credit cards issued (vs more than 4m for Nubank).

All in all, Nubank is making a big investment in Mexico, but for now it seems to be paying off, with Nubank taking the leadership among emerging Fintechs.

Stepping back and focusing on the market, Mexico shares a lot of characteristics with Brazil. The Top-5 banks hold a very large proportion of the market, fees and interest rates on loans are elevated, bank RoEs are high, and customer service poor.

However, the Mexican regulator has historically been a lot slower and less sophisticated than the Brazilian one, and has done a worse job at incentivizing competition and the digitalization of the economy. Also, credit cards in Mexico have a different structure than in Brazil, with retailers being reimbursed in 3 days from purchase date, as opposed to 30 days. Therefore, credit cards in Mexico are capital intensive, and it is incredibly costly for start-ups without a banking license (and hence the ability to accept deposits) to ramp up a successful credit card operation in Mexico.

As a result, today Mexico presents a situation similar to that in Brazil 10 years ago. Cash is still the primary transaction method and credit is restricted to high-income individuals. However, according to our conversations with industry participants, as it happened in Brazil in the mid 2010s, the economy is experiencing a strong digitalization wave that we believe constitutes a great hunting ground for Nubank.

When it comes to underwriting credit cards, banks in Mexico are much more conservative than in Brazil. For example, Mexican banks for the most part only issue credit cards to customers that have kept their payroll with them for at least 2 years. Nubank, on the other side, has a much more sophisticated underwriting operation, and is able to provide credit cards to consumers that never had a credit card before. - Former Head of Credit and Analytics at Nubank Mexico.

6. RoE, Profitability, Valuation and Long-Term Potential

To this point, we have long discussed Nubank’s runway for growth. In this section, we will argue that this growth will be achieved with a very high RoE. In particular:

I. RoE in the Brazilian operation is already as high as 60%.

II. Underlying earnings are higher than reported earnings.

III. In the long-term, earnings have the potential to reach ~$4/share (vs spot price of $11.76/share).

Starting with Return on Equity, Nubank printed 23% of consolidated RoE in Q4 2023 (fully loaded, after share based compensation and exceptionals). However, this figure is severely diluted by having (i) $2.4Bn in cash at the holding company in Cayman Islands and (ii) capital trapped in the loss-making Mexican and Colombian subsidiaries.

Every semester, Nubank files with the Brazilian Central Bank detailed financials for the Brazilian subsidiary. Using those filings, we can compute the evolution of RoEs presented below. Given Q4 was significantly more profitable than Q3, we can safely assume that RoE of the Brazilian Subsidiary is currently ~60%.

With that we do not intend to say that it would be prudent to distribute to shareholders the entire cash balance at the holding company, and we do not disregard the fact that the Mexican and Colombian subsidiaries are currently loss making. But we believe that the fact that the Brazilian banking subsidiary is able to achieve 60% RoE while both (i) comfortably meeting the regulatory capital requirements and (ii) achieving growth rates of ~60% p.a., is indicative of the long-term earnings potential of Nubank.

Also, note that management has repeated in multiple occasions that they do not expect to raise additional capital to support growth.

On another note, regarding underlying earnings, we believe that the IFRS treatment of loan loss provisions results in reported earnings that underestimate the true earning power of growth companies.

Under IFRS 9, a provision for the expected losses during the entire life of the loan needs to be expensed when the loan is first granted. That creates a revenue and expense recognition mismatch, whereby revenue (i.e. interest) is recognized through the entire life of the loan, while the expenses (i.e. loan losses) are recognized entirely at inception. That mismatch averages out for companies that do not grow, but severely penalizes earnings for growth companies like Nubank.

Nubank tracks the change in provisions due to growth and we believe that, adjusted for a 40% Tax rate in Brazil, should be added to net income to reflect the true steady-state earnings power of Nubank.

With this adjustment, Valuation is currently at 24x Q4 2023 Run Rate Earnings, which is the multiple we have used internally to value the business.

Note that we have not incorporated this adjustment into the RoE calculation. The reason is that overprovisioning has the effect of reducing earnings, but also book value, and therefore we should adjust for this effect both in the numerator and denominator. It would be hard to do with the available information, and the overall answer (that Nubank has a very large RoE in Brazil) would not change.

Finally, regarding the long-term earnings potential of Nubank, we think there is value in doing a back-of-the-envelope calculation on how profitable Nubank can become. Important to note that the below are by no means conservative assumptions, and are more an exercise of sizing the prize, as opposed to a business case we are fully underwriting. Our assumptions are the following:

I. Nubank can achieve 100m active customers in Brazil (mgmt. guidance, they are currently at 73m and adding 3-4m every quarter).

II. Nubank can achieve ARPAC of $25/month (mgmt. guides to $25-30, represents discount vs incumbents as seen on Figure 16). Note that mature cohorts already exceed that number, as shown in Figure 3.

III. That would translate to revenues in Brazil of $30Bn/year. This figure compares with $126Bn Retail Financial Services TAM in Brazil in 2021, as per Mgmt. analysis. That would represent a 24% market share, or 3 p.p. less than the percentage of the Brazilian population that, already today, use Nubank as primary bank account.

IV. Net Income margin can become ~30%. That compares with 25% for Nubank in Q4 2023 if adjusting for the impact of growth on provisions, and we therefore believe upside potential exists if further operating leverage materializes, as shown in Figure 26.

V. This leads to earnings in Brazil of ~$9Bn or ~$2/share.

$2/share is what we consider the full-potential earnings in Brazil. Outside of Brazil, mgmt. has stated that they believe they can become as large as in Brazil. On a GDP basis, Colombia and Mexico combined are similar to Brazil (Figure 20). However, their Retail Financial Services TAM is currently much smaller than Brazil ($51Bn vs $126Bn, as per Mgmt. analysis in 2021). The thesis is that the market will expand very meaningfully as the ongoing digitalization wave in Mexico progresses (see Section 5).

If we take Mgmt. at face value, we therefore arrive to long-term potential earnings of ~$4/share. As discussed, we do not necessarily endorse this figure, but we believe it serves as a calibration of the earnings potential of Nubank. Note that this figure does not include any underlying market growth, which is meaningful in Brazil, or expansion to additional countries.

In terms of the time required to achieve that number, we refer the reader again to the RHS of Figure 3. Note that cohorts take ~6 years to reach their full potential. In Brazil, Nubank already has a vast number of customers at different stages of maturity, and we therefore believe that in another 5-7 years, the business should not be far from its full potential. In Mexico and Colombia, expansion started more recently and therefore Nubank will need time to first recruit the customers and then let them mature. Hence full potential is likely to be 8-10 years away.

7. Competitive Position and Moat

In this segment we will address how Nubank competes with each of 3 main groups of competitors:

I. Incumbent banks

II. Other digital banks

III. Mercado Libre, through their fintech arm Mercado Pago

Starting with incumbent banks, we have long discussed Nubank’s lower-cost-to-serve advantage, and their willingness to pass most of these savings to its customers, creating a flywheel with larger scale feeding lower cost to serve and vice versa.

This flywheel is particularly strong for the low-income segment, where average tickets and credit balances are much lower and, therefore, Nubank’s advance has made it very hard for incumbent banks to serve this customer group profitably:

The whole market is trying to reposition towards high-income. I think low-income is a challenge for us and for the entire market. I think it is a major challenge and we do not have all the answers, but we are asking ourselves the questions now. We will only be able to afford to have a profitable low-income operation if we drop our cost to serve to a very low level. A 10 or 20% reduction will not be enough, it needs to be much lower. We need to redesign the entire value proposition, and also our brand positioning. – Banco Santander Brazil, Q3 2023 Earnings call.

We just want to stress, once more, that we believe an equally important differentiator lays on Nubank’s level of sophistication in underwriting credit, with mgmt. claiming to achieve 15-25% lower NPLs than traditional banks when underwriting comparable customers. Our conversations with industry participants seem to confirm this:

In Brazil, incumbent banks operate the business as they always have, hiring the same type of people from the same universities. Nubank brought a different kind since the beginning, when they set up the whole credit underwriting operation to look like Capital One. They brought a lot of talent form Capital One, and until today, for the past 10 years, the senior leadership of Nubank has always been Capital One formers. They brought something different to the market. – Former Credit Analyst in Brazil at Nubank.

We finally note that Nubank also has developed a highly regarded consumer brand, given it was the first player to provide radically lower fees and better terms of service for their customers, creating strong loyalty vs incumbents. The reader can imagine, for example, how customers in Mexico feel today towards Nubank after being offered 15% for their deposits, vs 3-4% historically by incumbent banks.

On the negative, Nubank faces a higher cost of deposits, but in Brazil the difference is narrowing as Nubank’s offering expands, as shown on Figure 11.

When competing with other digital banks, we believe that credit underwriting becomes the biggest moat. Setting up a successful credit operation is incredibly complex, and we encourage the reader to try to find a start-up in the US or Europe that has scaled a big consumer credit portfolio.

Also, Nubank has currently been underwriting credit for 10 years and has therefore lived through 3 credit tightening waves (the 2014 Brazilian economic crisis, Covid, and the credit tightening of 2022) while carrying an outstanding credit portfolio of billions of dollars spread across tens of millions of customers. That has provided a massive amount of data on consumer behaviour and stress tested its models. A newer digital bank, even if it was able to set up the credit models in the same way that Nubank did, would face a major disadvantage in terms of the amount of data it controls (note that the number of data points that can be transferred with Open Finance is relatively small and limited to certain categories).

Given most digital banks are not listed and no public information is available, the best KPI we have found to gauge their success is the growth in the number of Monthly Active Users of their mobile apps, as reported by Sensor Tower. As can be seen, all other start-ups with the exception of Mercado Pago, are performing poorly, and our conversations with industry participants point to the inability to offer higher credit limits to their customers as the main reason.

Finally, when it comes to Mercado Libre, we believe it is the most formidable competitor Nubank faces. Founded in 1999 in Argentina, Mercado Libre has evolved to become the largest e-commerce platform in Latin America, comfortably beating Amazon. Over time, Mercado Libre expanded into Fintech by launching Mercado Pago, which originally was focused on offering 3rd-party e-commerce sites the capabilities to accept online payments.

In recent years, Mercado Pago has entered the space of retail financial services, where it competes head on with Nubank in Mexico and Brazil. Through their mobile app, Mercado Pago offers a bank account, debit cards and credit cards. Also, they have a strong BNPL offering, mostly catered to providing credit to consumers who purchase products on Mercado Libre’s e-commerce site, but also open to 3rd-Party e-commerce vendors.

Mercado Pago has two obvious advantages when competing with Nubank as a bank account:

I. The opportunity to attract customers by bundling financial services with their e-commerce site (in the same way that, for example, Amazon Prime Video competes with Netflix).

II. Possessing customer data about their e-commerce behaviour, which Nubank does not possess, and which could be used to better underwrite credit.

On the other hand, Mercado Pago has three obvious disadvantages when competing with Nubank:

I. They do not possess a banking license in Brazil or Mexico, and therefore they cannot use deposits to fund loans.

II. They have historically struggled with underwriting credit, do not have a long history of cohort performance data, and are currently experiencing very high levels of NPLs.

III. Their offering in Brazil is a lot less developed than Nubank’s, given their focus in multiple verticals (e-commerce, payments and credit) and geos (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, etc). They lack, for example, Pix financing, payroll loans, an investment account, or a high-income credit card offering with cash-back.

As of today, there is no question, in our view, that Nubank is far ahead of Mercado Pago when it comes to providing end-to-end financial services to individuals, particularly in Brazil. Note that Mercado Libre “only” has 54 million e-commerce users spread across Mexico, Brazil and Argentina, which have a combined population of 390 million. For those that are not frequent customers of Mercado Libre, we believe that Nubank is likely to remain a superior proposition for the foreseeable future. For those that are frequent customers of Mercado Libre, on the other hand, we can imagine a scenario where the race gets tighter over time.

We chiefly respect Mercado Pago, and we have no doubt that Mercado Libre will grow over time, and most likely, eventually be able to underwrite credit proficiently. We believe that the market is large enough to accommodate both Nubank and Mercado Libre, and remind the reader that our long-term potential for Nubank assumes a market share of under 24% ($30Bn Revenues in Brazil, vs $126Bn Retail Financial Services TAM as per management analysis), leaving plenty of room for Mercado Pago to thrive.

8. Risks

We acknowledge that an investment of these characteristics calls for a higher-than-usual attention to the “Risks” section of the investment thesis. However, we believe that Nubank is a safer investment than it appears at first glance. In our view, the following are the main risks Nubank faces:

I. Macroeconomic risk

II. Geopolitical risk

III. Regulatory risk

IV. Credit risk

V. Liquidity and Run-on-the-Bank risk

Starting with macroeconomic risk, there is no doubt that LatAm is a volatile market. Brazil, in particular, is etched in the recent memory of several investors given the country lived, in 2014, one of the most devastating crises of its history, with Brazilian equities and leveraged buyouts severely underperforming their US counterparts in the period 2012-2017. The origin of this crisis is primarily attributed to poor economic policy during the government of Dilma Rousseff, coupled with the 2014 commodity price shock that negatively affected Brazil’s exports. Between 2014 and 2016, GDP fell by 8.1%, making it the second worst peak-to-trough recession on Brazil’s record.

Note that the 2014 crisis led to a strong currency devaluation. However, over time, due to significant inflation, even if the currency devaluated, Brazil GDP in USD has not fallen with the Real. On a longer time horizon, GDP in 2023 is 1.6x the pre-GFC figure, when compared in USD terms. In that same period, the Brazilian Real has depreciated by over 50%.

We argue that this is the prevailing expression of financial crises in Latin America. Over time, the affected country continues to produce a broadly similar amount of total output, and the strong devaluation of the currency leads to an offsetting amount of inflation. The USD figure, which is the best gauge of true economic output, is therefore likely to remain broadly stable.

We believe Argentina is a good case study for this phenomenon, with a GDP in USD that is volatile but stable over time, even if the Argentinian Peso depreciated by 95% in the last 5 years.

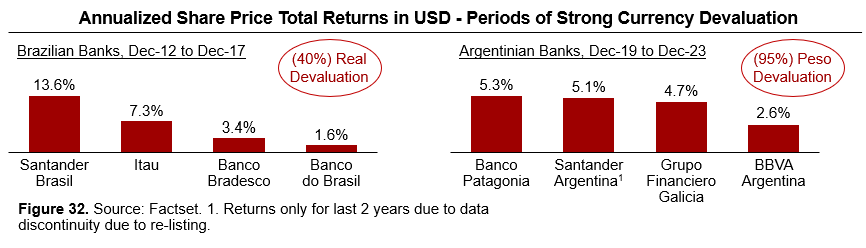

The key question, however, is how banks perform within this economic backdrop. As can be seen, banks have performed historically particularly well in high inflation environments, even when observing results on a USD basis, which is an unintuitive result. The reason for that is twofold:

I. Bank growth is strongly linked to inflation. Interchange fees is the most obvious link, but also higher loans can be expected if the value of currency falls in relation to goods and services.

II. Banks in LatAm present high RoEs, and can hence grow with inflation without excessive capital consumption.

As discussed in Section 6, Nubank has the highest RoE among all major banks in Brazil (60% vs ~20% on average), and thus we believe it is primely positioned to weather a period of high inflation and currency devaluation.

Also, note that while Nubank is currently primarily focused on Brazil, it is currently scaling its Mexican operations and, if successful, it would provide a source of macroeconomic diversification. Mexico has been somewhat more stable than Brazil in recent years, and its performance below serves as one more example of how USD-based GDPs in Latin America are stable over time, even if their currencies lose value.

As a final note on Macroeconomy, given we have used the comparison with Argentina as an extreme example of hyperinflation, we feel it is appropriate to point that Brazil is structurally a much better economy, because:

I. The Argentinian government has historically borrowed in USD, as opposed to local currency, while the Brazilian one has very little foreign currency debt.

II. The Argentinian Central Bank has no foreign currency reserves, vs significant reserves at the Brazilian Central Bank.

Also, Brazil presents a currency tailwind because it is significantly expanding its offshore oil drilling operations, which creates a positive impact on the Trade Balance, which has turned positive in recent years.

By no means do we claim to be able to forecast the Brazilian macroeconomic environment, but with the above we just seek to dispel the notion that the country is “un-investable”, which is a view that many fellow investors have expressed to us in recent years.

Moving on to the next type of risk, we believe what we have called geopolitical risk is an unlikely one, but one that if it materialized could have significant consequences. Brazil has been a democracy since 1985. However, its current president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is a big proponent of the BRICS alliance (Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa). As such, he has publicly stated he plans to visit Russia in 2024, rejected to enforce the international arrest warrant pending on Vladimir Putin were he to visit Brazil for the G20 that will occur in November, and formed close ties with China, which is the biggest importer of Brazilian goods. There is no current prospect of Brazil facing sanctions from the US, but in an increasingly divided world, we would feel our funds would be less likely to be caught between international sanctions if they were invested in a country with a different set of strategic allies. We remind the reader, however, that Nubank has its primary listing in the NYSE.

A far more tangible one, we believe Nubank has a moderate level of regulatory risk. As we discussed in Section 2, the government and the BCB are both laser-focused on promoting competition and ensuring that consumers experience a lower level of interest rates and fees. In the last 2 years, at least three pieces of legislation have been passed which impacted banks’ profitability:

I. Implementation of an interest rate cap of 1.7% p.m. for certain types of payroll loans, in particular those backed by social security (as opposed to government salaries). That did not affect Nubank, given it was not yet offering payroll loans. Also, Nubank is currently offering a rate of 1.4% for this specific type of loan, well below the cap.

II. Reduction in the interchange fee for a certain type of debit cards, called prepaid cards. The change was implemented in April 2023, and the interchange fee was capped at 0.7%, down from ~1.2%. That did affect Nubank, erasing ~2% of its revenues overnight.

III. As of January 2024, a new rule came into effect that limited the total amount of interests to be paid on a credit card transaction to 100% of the original purchase value. As discussed, Nubank is very proactive in reducing the revolving portion of the credit card balance, which is the main cause of excessive rates (see discussion on Section 2). The impact on revenue will be negligible, with Nubank having published that the percentile 99th of credit card transactions that pay the most interest is at 40.5% of the original purchase price, far below the 100% cap.

We agree with the government approach to limiting what we believe are abusive practices. We recognize that some of the future pieces of legislation might be a headwind for Nubank’s profitability, but drive comfort from two thoughts:

I. Nubank’s model is predicated on offering the lowest fees and interest rates in the market, and will thus be one of the last banks to be affected.

II. Nubank’s RoE is currently at 60% and growing, vs traditional banks at ~20% and declining.

Both things considered, we believe that if more stringent legislation is passed, it will far earlier drive the incumbent banks to not earn their cost of capital than it will meaningfully affect Nubank’s profitability. We do not necessarily dislike a world where incumbents are forced to pullback and Nubank exchanges lower unit profits for higher scale, with the positive effect that this would have on Nubank’s competitive moat. Even if we consider the behaviour of the Regulator certainly a risk, we believe it is unlikely to become a severe headwind for the business.

On a different note, regarding credit risk, a lot has been written in this report about Nubank’s underwriting capabilities. Beyond the fact that, as discussed, their credit models have been stress-tested across 3 different credit tightening cycles, two elements provide additional comfort:

I. Nubank is very well provisioned, with a provision to 90+ NPLs coverage of 225%.

II. It has ~3.5x more capital than the regulatory minimum which, together with provisions, provides for a large loss absorption capacity.

As for liquidity risk, it is important to note that financial instability in Latin America has led to bank runs before (e.g. “Corralito” in Argentina in 2001). Brazil has not seen this dynamic to date, but was there to be widespread financial panic, we believe Nubank would be likely to be one of the last banks standing:

I. Loan-to-deposit ratio stands unusually low at 34%.

II. Cost of deposits for Nubank is ~80% of the Brazilian SOFR-equivalent, called CDI. A run on the bank that brought deposits to zero would force Nubank to, at most, borrow $8Bn (the amount of interest-earnings loans outstanding) at 100% of CDI, which would have an impact on profits of ~$40m per quarter vs borrowing at 80% of CDI. That compares to earnings of ~600m in Q4-2023, when adjusted for IFRS 9 impact of growth on provisions.

III. Nubank’s loans are very short term (6 months on average) and, if needed, Nubank could thus decrease its liquidity needs quickly.

For all these reasons, and strictly in terms of credit and liquidity risk, Nubank is the bank with the least amount of existential risk that we have encountered in a while.

9. Conclusion

We encourage the reader to think what the appropriate valuation would be for a US-based company with the following characteristics:

I. 27% of the adult population use it as their primary banking provider.

II. Has 3x the RoE of the best incumbent banks, like Bank of America.

III. Continues to grow inside the US at ~60% per annum.

IV. It has found a second market somewhere with the same size and conditions as the US, and is ramping up quickly from a very low base.

We acknowledge the US is a much better economy than Brazil and Mexico, but at 24x Q4-2023 Run Rate Earnings (after SBC and exceptionals) we feel we are appropriately remunerated for the risk. We believe this is a truly unique situation and we are therefore proud owners of Nubank.

this was fantastic, thank you for sharing